However, given two amplifiers with identical, verifiable objective specifications, listeners may strongly prefer the sound quality of one over the other. This is actually the case in the decades old debate [some would say jihad] among audiophiles involving vacuum tube versus solid state amplifiers. There are people who can tell the difference, and strongly prefer one over the other despite seemingly identical, measurable quality. This preference is subjective and difficult to measure but nonetheless real. Individual elements of subjective differences often can be qualified, but overall subjective quality generally is not measurable. Different observers are likely to disagree on the exact results of a subjective test as each observer's perspective differs. When measuring subjective qualities, the best one can hope for is average, empirical results that show statistical significance across a group.

Perceptual codecs are most concerned with subjective, not objective, quality. This is why evaluating a perceptual codec via distortion measures and sonograms alone is useless; these objective measures may provide insight into the quality or functioning of a codec, but cannot answer the much squishier subjective question, "Does it sound good?". The tube amplifier example is perhaps not the best as very few people can hear, or care to hear, the minute differences between tubes and transistors, whereas the subjective differences in perceptual codecs tend to be quite large even when objective differences are not.

A loss of fidelity implies differences between the perceived input and output signal; it does not necessarily imply that the differences in output are displeasing or that the output sounds poor (although this is often the case). Tube amplifiers are not higher fidelity than modern solid state and digital systems. They simply produce a form of distortion and coloring that is either unnoticeable or actually pleasing to many ears.

As compared to an original signal using hard metrics, all perceptual codecs [ASPEC, ATRAC, MP3, WMA, AAC, TwinVQ, AC3 and Vorbis included] lose objective fidelity in order to reduce bitrate. This is fact. The idea is to lose fidelity in ways that cannot be perceived. However, most current streaming applications demand bitrates lower than what can be achieved by sacrificing only objective fidelity; this is also fact, despite whatever various company press releases might claim. Subjective fidelity eventually must suffer in one way or another.

The goal is to choose the best possible tradeoff such that the fidelity loss is graceful and not obviously noticeable. Most listeners of FM radio do not realize how much lower fidelity that medium is as compared to compact discs or DAT. However, when compared directly to source material, the difference is obvious. A cassette tape is lower fidelity still, and yet the degredation, relatively speaking, is graceful and generally easy not to notice. Compare this graceful loss of quality to an average 44.1kHz stereo mp3 encoded at 80 or 96kbps. The mp3 might actually be higher objective fidelity but subjectively sounds much worse.

Thus, when a CODEC must sacrifice subjective quality in order to satisfy a user's requirements, the result should be a difference that is generally either difficult to notice without comparison, or easy to ignore. An artifact, on the other hand, is an element introduced into the output that is immediately noticeable, obviously foreign, and undesired. The famous 'underwater' or 'twinkling' effect synonymous with low bitrate (or poorly encoded) mp3 is an example of an artifact. This working definition differs slightly from common usage, but the coined distinction between differences and artifacts is useful for our discussion.

The goal, when it is absolutely necessary to sacrifice subjective fidelity, is obviously to strive for differences and not artifacts. The vast majority of CODECs today fail at this task miserably, predictably, and regularly in one way or another. Avoiding such failures when it is necessary to sacrifice subjective quality is a fundamental design objective of Vorbis and that objective is reflected in Vorbis's channel coupling design.

Channel interleaving may be applied directly to more than a single channel and polar mapping is hierarchical such that polar coupling may be extrapolated to an arbitrary number of channels and is not restricted to only stereo, quadriphonics, ambisonics or 5.1 surround. However, the scope of this document restricts itself to the stereo coupling case.

The basic idea behind any stereo coupling is that the left and right channels usually correlate. This correlation is even stronger if one first accounts for energy differences in any given frequency band across left and right; think for example of individual instruments mixed into different portions of the stereo image, or a stereo recording with a dominant feature not perfectly in the center. The floor functions, each specific to a channel, provide the perfect means of normalizing left and right energies across the spectrum to maximize correlation before coupling. This feature of the Vorbis format is not a convenient accident.

Because we strive to maximally correlate the left and right channels and generally succeed in doing so, left and right residue is typically nearly identical. We could use channel interleaving (discussed below) alone to efficiently remove the redundancy between the left and right channels as a side effect of entropy encoding, but a polar representation gives benefits when left/right correlation is strong.

*Because the Vorbis model supports a number of different possible stereo models and these models may be mixed, we do not use the term 'intensity stereo' talking about Vorbis; instead we use the terms 'point stereo', 'phase stereo' and subcategories of each.

The majority of a stereo image is representable by polar magnitude alone, as strong sounds tend to be produced at near-point sources; even non-diffuse, fast, sharp echoes track very accurately using magnitude representation almost alone (for those experimenting with Vorbis tuning, this strategy works much better with the precise, piecewise control of floor 1; the continuous approximation of floor 0 results in unstable imaging). Reverberation and diffuse sounds tend to contain less energy and be psychoacoustically dominated by the point sources embedded in them. Thus, we again tend to concentrate more represented energy into a predictably smaller number of numbers. Separating representation of point and diffuse imaging also allows us to model and manipulate point and diffuse qualities separately.

Vorbis uses a mapping that preserves the most useful qualities of polar representation, relies only on addition/subtraction, and makes it trivial before or after quantization to represent an angle/magnitude through a one-to-one mapping from possible left/right value permutations. We do this by basing our polar representation on the unit square rather than the unit-circle.

Given a magnitude and angle, we recover left and right using the following function (note that A/B may be left/right or right/left depending on the coupling definition used by the encoder):

if(magnitude>0)

if(angle>0){

A=magnitude;

B=magnitude-angle;

}else{

B=magnitude;

A=magnitude+angle;

}

else

if(angle>0){

A=magnitude;

B=magnitude+angle;

}else{

B=magnitude;

A=magnitude-angle;

}

}

The function is antisymmetric for positive and negative magnitudes in

order to eliminate a redundant value when quantizing. For example, if

we're quantizing to integer values, we can visualize a magnitude of 5

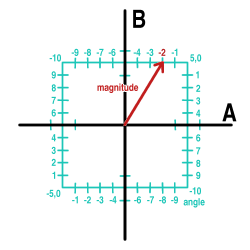

and an angle of -2 as follows:

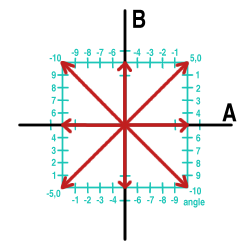

This representation loses or replicates no values; if the range of A and B are integral -5 through 5, the number of possible Cartesian permutations is 121. Represented in square polar notation, the possible values are:

0, 0 -1,-2 -1,-1 -1, 0 -1, 1 1,-2 1,-1 1, 0 1, 1 -2,-4 -2,-3 -2,-2 -2,-1 -2, 0 -2, 1 -2, 2 -2, 3 2,-4 2,-3 ... following the pattern ... ... 5, 1 5, 2 5, 3 5, 4 5, 5 5, 6 5, 7 5, 8 5, 9...for a grand total of 121 possible values, the same number as in Cartesian representation (note that, for example, 5,-10 is the same as -5,10, so there's no reason to represent both. 2,10 cannot happen, and there's no reason to account for it.) It's also obvious that this mapping is exactly reversible.

Entropy coding the results, then, further benefits from the entropy model being able to compress magnitude and angle simultaneously. For this reason, Vorbis implements residuebackend #2 which preinterleaves a number of input vectors (in the stereo case, two, A and B) into a single output vector (with the elements in the order of A_0, B_0, A_1, B_1, A_2 ... A_n-1, B_n-1) before entropy encoding. Thus each vector to be coded by the vector quantization backend consists of matching magnitude and angle values.

The astute reader, at this point, will notice that in the theoretical case in which we can use monolithic codebooks of arbitrarily large size, we can directly interleave and encode left and right without polar mapping; in fact, the polar mapping does not appear to lend any benefit whatsoever to the efficiency of the entropy coding. In fact, it is perfectly possible and reasonable to build a Vorbis encoder that dispenses with polar mapping entirely and merely interleaves the channel. Libvorbis based encoders may configure such an encoding and it will work as intended.

However, when we leave the ideal/theoretical domain, we notice that polar mapping does give additional practical benefits, as discussed in the above section on polar mapping and summarized again here:

Overall, this stereo mode is overkill; however, it offers a safe alternative to users concerned about the slightest possible degredation to the stereo image or archival quality audio.

It's often quoted that the human ear is nearly entirely deaf to signal phase above about 4kHz; this is nearly true and a passable rule of thumb, but it can be demonstrated that even an average user can tell the difference between high frequency in-phase and out-of-phase noise. Obviously then, the statement is not entirely true. However, it's also the case that one must resort to nearly such an extreme demostration before finding the counterexample.

'Phase stereo' is simply a more aggressive quantization of the polar angle vector; above 4kHz it's generally quite safe to quantize noise and noisy elements to only a handful of allowed phases. The phases of high amplitude pure tones may or may not be preserved more carefully (they are relatively rare and L/R tend to be in phase, so there is generally little reason not to spend a few more bits on them)

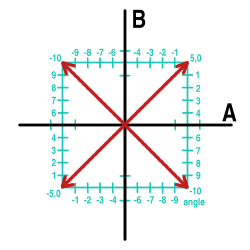

Left and right may be in phase (positive or negative), the most common case by far, or out of phase by 90 or 180 degrees.

It is also the case that near-DC frequencies should be encoded using lossless coupling to avoid frame blocking artifacts.

Ogg is a Xiphophorus effort to

protect essential tenets of Internet multimedia from corporate

hostage-taking; Open Source is the net's greatest tool to keep

everyone honest. See About

Xiphophorus for details.

Ogg is a Xiphophorus effort to

protect essential tenets of Internet multimedia from corporate

hostage-taking; Open Source is the net's greatest tool to keep

everyone honest. See About

Xiphophorus for details.

Ogg Vorbis is the first Ogg audio CODEC. Anyone may freely use and distribute the Ogg and Vorbis specification, whether in a private, public or corporate capacity. However, Xiphophorus and the Ogg project (xiph.org) reserve the right to set the Ogg/Vorbis specification and certify specification compliance.

Xiphophorus's Vorbis software CODEC implementation is distributed under a BSD-like License. This does not restrict third parties from distributing independent implementations of Vorbis software under other licenses.

OggSquish, Vorbis, Xiphophorus and their logos are trademarks (tm) of Xiphophorus. These pages are copyright (C) 1994-2001 Xiphophorus. All rights reserved.